Who’s Afraid of Community Control?

by Erica Caines | Originally Published Thursday – March 10, 2022 on Hood Communist

Over the last year, in response to right-wing reactionaries, Critical Race Theory (CRT) has been centered as the primary fight for Africans in the U.S. From state to state, legislation has been passed to ban books written by Africans that detail the U.S’ racial history. As such, the discussion on the education of African children has been put front and center while the reality of how African children are taught in U.S colonial schools is obfuscated.

As with many things, conversations on CRT are being led by reactions to the right-wing so many don’t have a clear understanding of what CRT is. As Dr. Charisse Burden Stelly has noted, “[CRT] just means everything and nothing. Like communism, like radicalism, like ANTIFA, critical race theory is just another boogey[man].” Although wildly depicted by people like Candace Owens as “ the new Jim Crow,” CRTs examination of race has origins in assessing white supremacy and the law.

While the history of who coined the term, “critical race theory” remains contested, according to Derrick Bell’s “Who’s Afraid of Critical Race Theory?” (1995), CRT is, “a body of legal scholarship, now about a decade old, a majority of whose members are both existentially people of color and ideologically committed to the struggle against racism, particularly as institutionalized in and by law.” This framework for legal analysis emerging from academic insurrectionist concepts put forth by liberal scholars like Bell, Kimberle Crenshaw, and Richard Delgado (among others ) in the 1980s, challenged core ideas that race is a social construct, and that racism is not just the product of individual bias or prejudice, but also structurally embedded in legal systems and policies.

Critical Race Theory, according to scholars like Prof. Gerald Horne, is the response to the Marxist formation of Critical Legal Studies. Horne says it is curious that the right assesses CRT as a branch of Marxism, “because the founders consciously and intentionally set out to create a way of looking at the law that would shield them from pro-communist charges, which I think is quite revealing because it helps us to realize that these anti-communist charges are more an attack on any kind of challenge to the status quo, which leads to the moral panic that’s now unfolding about critical race theory, the fact that supposedly it can’t be taught in K-12 education.”

The reaction from the right triggering a reaction from African parents disregards that CRT is, in fact, an academic framework and not anything taught in K-12 public education. The narratives supporting the idea that CRT is simply “discussing race” allowed for any discussion on race in school to be collapsed within that framework. So not only does legislation get pushed to protect “white feelings”, but more importantly, serve as a way to dismiss institutional criticism of white supremacy and the state promoting anti-intellectualism and rejection of primary sources in favor of a superficial race war. If African parents were to step back from the confusion of this reaction to reactionary discourse, they could be real about the constrictions on what their children are learning long before CRT came under attack. The use of Black History Month serves as an example of the warped ways African children are taught.

When mainstream media remembers that Africans in the US are parents too, and ask for their thoughts on the anti-CRT legislation, the underlying message is that African parents want the ability to have a say in what their children learn. However, being trapped into the reactionary discourse of anti-CRT, African parents are moved away from solutions like community control of schools. Community Control of Schools (CCOS) attempts to redefine the relationship that colonized parents have with school systems, pushing for decision-making power in the education of their children.

The anti-CRT discourse assists in burying histories of large-scale fights for CCOS which would serve as blueprints for how reactionary conversations about public education should be approached. More than a decade after the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, the state of school integration was failing. The 1968 NYC Teachers Union standoff in Ocean- Hill Brownsville sought to change that. Establishing locally elected school boards, the colonized community came to a partial realization of self-determination. According to Dr Marilyn Gittell’s Chronicle of Conflict in 1969, “The school crisis in New York City made front page copy for every major newspaper in the country for over a month… Ocean Hill-Brownsville became a symbol for Black people. . .They identified strongly with what they perceived as an assertion of Black independence. Large segments of the white population, on the other hand, identified with the teachers. . . They resented the militancy of a Black community which dared to change long-established precedents. These polarized responses were themselves a reflection of a fundamental conflict in American urban communities elaborately explored in the Kerner Commission report.” Ironically, anti-CRT, for the right, has always been about the ability to control what their children learn yet Africans are moved away from the idea in favor of inclusionary rhetoric based on a falsified promise of equality that was sure to never include equity.

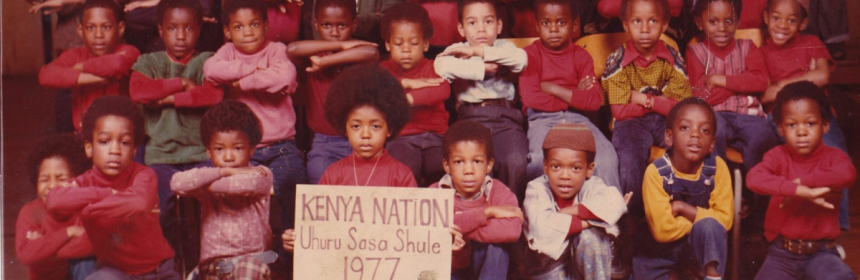

Supporting small-scale attempts (like Saturday schools, community schools, home-schooling and, even Liberation Through Reading) to control the education of our African children is one step to advance the clarity around the question of self-determination creating foundations and networks to build towards getting back to community control efforts. Solely rejecting anti-CRT will not advance the question of self-determination. Beyond debates, reacting to anti-CRT has not and can not change the material reality of the education African children receive within the colonial context of the US that is predicated on creating good patriots and obedient workers. That is something Africans, for the sake of our children, will have to organize to build.